In November 1986 the two parishes of St.Peter and St.Clement were united to form the new parish of St Clement with St Peter. Both congregations continued to worship in their respective buildings until March 1996 until when no longer able to use St. Peter’s church both congregations came together under the roof of St.Clement’s.

THE OLD ST. PETER’S

In the 1850’s the parish of St. Giles, Camberwell extended to where the Crystal Palace once stood. At that time there was a great influx of residents into the area and the parishes of St. John, East Dulwich and St. Peter, Dulwich Common were formed out of the parish of St. Giles in 1865 and 1867 respectively. After using a temporary building for a few years, St. Peter’s church was built in 1874.

In the 1850’s the parish of St. Giles, Camberwell extended to where the Crystal Palace once stood. At that time there was a great influx of residents into the area and the parishes of St. John, East Dulwich and St. Peter, Dulwich Common were formed out of the parish of St. Giles in 1865 and 1867 respectively. After using a temporary building for a few years, St. Peter’s church was built in 1874.

The picture of the inside of St.Peter’s Church is from a watercolour dated 1874

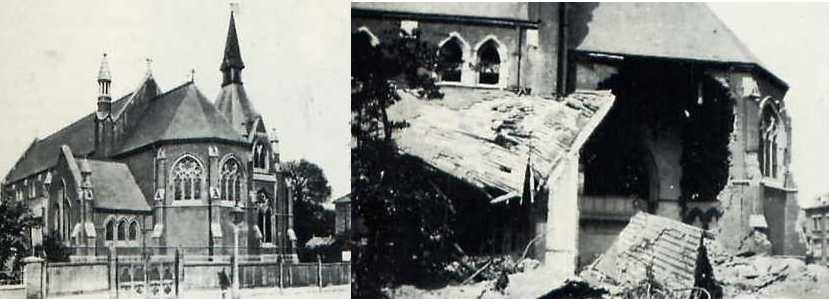

St. Clement’s was started in the 1870’s by members of St. John’s, East Dulwich as a mission church in Hindmans Road. It became a separate parish in 1883 when the first Vicar was appointed, and by 1885 a large new church had been built. That church was destroyed by enemy action in 1940, and after the war the present St. Clement’s was built. It was consecrated in September 1957.

The building is of modern design on a slightly elevated and generally rectangular site with a separate prefabricated church hall at the rear (west end). There is a tower and two storey galleried area at the west end (main entrance) and single storey ancillary accommodation with chapel, wrapped around the east end. The church itself has a nave with aisles and is of pointed arched, or “keel” shaped section.

Above the altar in the east wall is one of the earliest examples of coloured glass and concrete design.

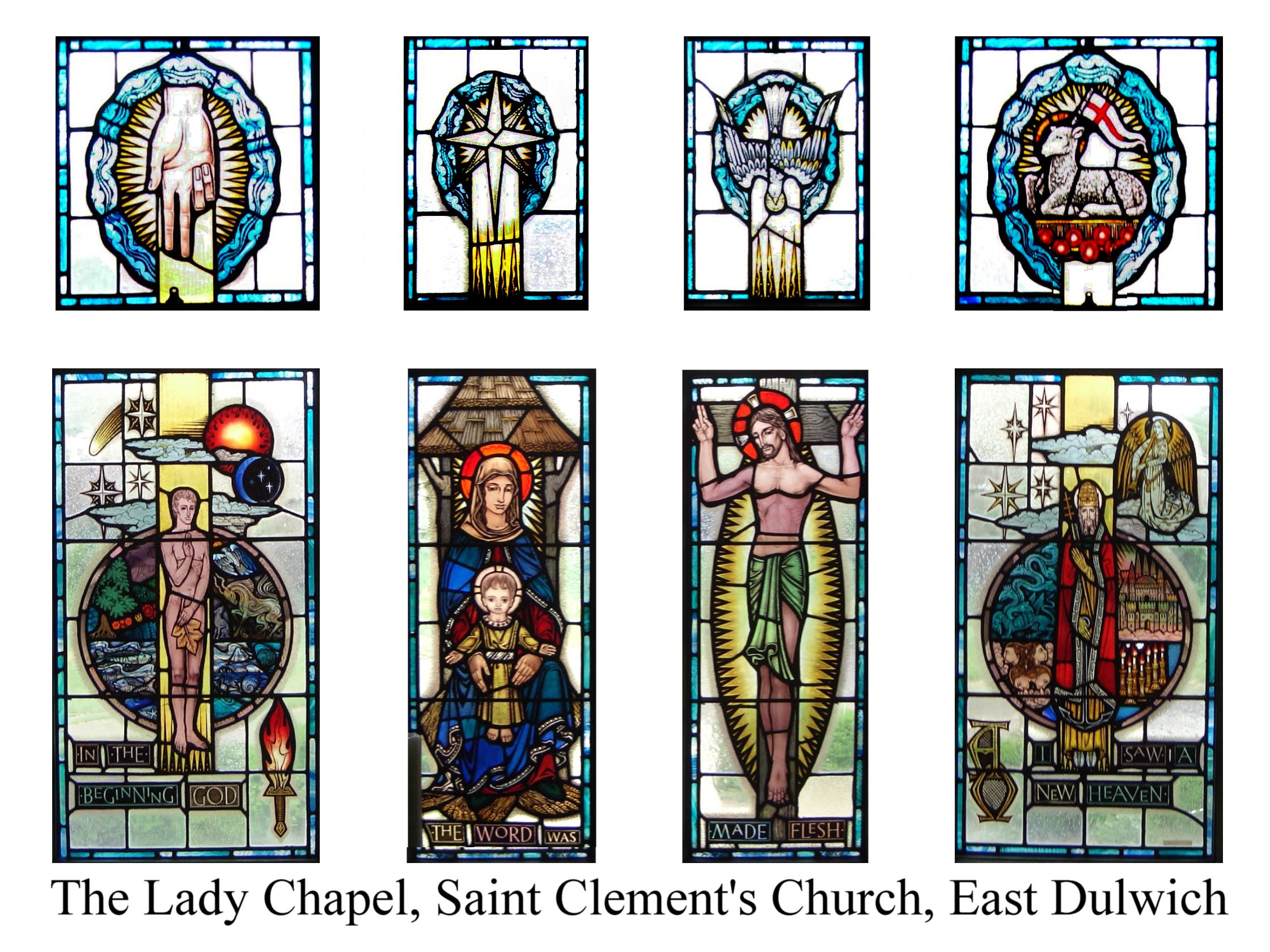

The chapel is a very intimate and sunlit space with windows of stained glass in leaded lights set into metal casements.

Link http://stclementwithstpeter.btck.co.uk/About%20us

Copyright – St Clements with St Peter,Dulwich

A short history

Up until 1827 the hamlet of East Dulwich was part of the large and ancient parish of St Giles, Camberwell. This originally covered the whole of Camberwell, Peckham, Dulwich and East Dulwich. The hamlet was surrounded by farmland, pasture and market gardens. It was thought that the people who lived and worked on the farms were too few and scattered to warrant a church of their own and consequently they had to make the trek over Dog Kennel Hill to St Giles to attend services.

Up until 1827 the hamlet of East Dulwich was part of the large and ancient parish of St Giles, Camberwell. This originally covered the whole of Camberwell, Peckham, Dulwich and East Dulwich. The hamlet was surrounded by farmland, pasture and market gardens. It was thought that the people who lived and worked on the farms were too few and scattered to warrant a church of their own and consequently they had to make the trek over Dog Kennel Hill to St Giles to attend services.

East Dulwich Chapel

However the populace was growing and in 1827 Thomas Baily, a large landowner in East Dulwich, decided that St Giles was too far away to serve the spiritual needs of the people. At his own expense and on his own land he built the East Dulwich Chapel. This was on the corner of what is now Tintagel Crescent facing Goose Green and it became a chapel-of-ease for St Giles. (A chapel-of-ease was subordinate to the mother church but built for the ease of the parishioners so they did not have to travel great distance to attend church.) Thomas Baily conveyed the chapel, with the land on which it stood, to Trustees which included his son, Farmer Baily of Hill Place near Tonbridge, his brother William, Robert Hichens and two others. The first minister was the Revd Matthew Anderson who left in 1844 and was followed by the Revd John Roberts Oldham (1845 to 1858) and then the Revd William Foster Elliot (1858 to1864). By the time Revd Foster Elliot arrived the population of East Dulwich was about 800 people.

A New Church

In 1861 it became clear that the chapel was not large enough for the growing population of the district, and in October of that year a meeting was held in the National School Room (Troy Town) to decide what was to be done. After an address by the Revd Foster Elliott a Church Building Committee was formed. A subscription list was opened by Mr R. Hichens with a donation of £1,000. He was also appointed Chairman of the Committee with John Scott (shawl merchant) as Treasurer and Henry John Puckle as Secretary. At a meeting of the building committee held a week later, it was resolved to offer the position of architect to Charles Baily, “in consideration of the long connection of his family with the District and as son of the original founder of the Chapel “. St John’s is believed to be the only church Charles Baily designed. It had been originally intended to build the new Church on the site of the existing Chapel, but sufficient room for the larger building could not be found. The problem was solved by Lord Chief Justice Charles Jasper Selwyn presenting the site on which the Church now stands. The architect’s plan for a Church to contain 845 sitting was then approved by the Committee. The estimate for the total cost of building the Church and fitting it for divine worship was £6,658.13.7. People seem to have subscribed generously towards the cost, 43 of the poorer families contributed over £350 between them. A few persons tried to attach conditions to their offerings for example a gentleman desiring curtains to his pew was refused. The Vicar undertook as his own subscription to the Church to provide the pews with appropriate cushions. The Church was consecrated by the Bishop of Winchester on 16 May 1865. Baily had designed a church in the Gothic style of the middle ages which was very popular with the Victorians at that time. It was once described as being like a French, early 13th century church. The tower, spire and apse that you see today are all original as is the clock which dates from 1864. The dial plate is 6′ 6″ in diameter and the clock strikes the hour on a bell that weighs ten hundredweight. It was manufactured by John Moore of Clerkenwell. The Sacristy was added in 1883, the Vestry in 1914.

The War Years and Rebuilding

In World War II St John’s Church was practically destroyed. The Revd Frank Bishop, vicar 1939 to ’45, described what happened. ‘On October 19th, 1940, a load of incendiaries was dropped over Goose Green and four separate fires were started in the church roof. With the help of the National Fire Service men stationed in Adys Road School, we managed to get them all out, and soon had the roof repaired and the church clean. On Sunday, December 8th, however, another load of a larger variety, some of which were explosive, descended. We were inside the church within one minute of their coming down. But only one had come through the roof. Many must have remained in it, for almost at once, it was alight from end to end. There were fires everywhere that night, and it was three quarters of an hour before the first appliance arrived and about another four or five hours before the firemen had got the fire out. Meanwhile we saved what we could from the church and emptied the vestries lest the fire should spread to them.’ Within two days the vestry had been furnished as a chapel and weekday services were held there until the church was rebuilt. The crucifix from the vestry chapel altar now hangs at the back of the pulpit. Sunday services for the next ten years were held at the Church of the Epiphany where, as Frank Bishop continued, ‘there was no air raid shelter, as we regarded the surface shelters alongside as meant for the residents in Bassano Street. In the darkest days of the war St John’s congregation never despaired of rebuilding the church. In the years that followed there were enormous fundraising efforts, including annual Gift Days, which prompted extremely generous contributions (over £1,900 in 1950). War Damage Compensation covered only part of the costs. The estimated amount to be raised by the congregation was at first £10,000 but was finally at least £15,000, a vast sum considering the difference in monetary value over 50 years ago. The achievement owed much to the zeal and energy of the vicar, the Revd Charles McKenzie who, as he wrote in 1952, had never worried about getting the money since, ‘if you trust in God, the money will be found to do God’s work’. The tower had, miraculously, survived the war. The original 1864 clock was set going again and by September 1948 was striking the hours, ‘to show that St John’s was very much alive’. In January 1947 the eminent architect, J.B. Sebastian Comper, son of the famous Sir Ninian Comper (who in fact designed many of the features used in the restoration of the building), had been appointed to be responsible for rebuilding the church. As Red McKenzie wrote in 1951, ‘It is doubtful whether a happier choice could have been made – in days when building anything is restricted by incredible regulations, when every quality of character is needed to achieve one’s aim, the respect and affection which the parish has for Mr Comper is something deeper and more appreciative of higher values than even the building which his genius has created.’ The first work on the church was the restoration of the apse, which had not been destroyed by the bombing. The architect had to obtain ‘a licence for second-hand seasoned wood’, in those difficult post-war years when all building materials were in short supply. The baldachino, over the high altar, was built not of wood but of plaster. Rebuilding the rest of the church started in earnest in August 1949. By April 1950 the chancel arch was complete and work begun on the nave. A year later the whole building was ready for use and on 5th May 1951 the Lord Bishop of Southwark, the Rt Revd Bertram Simpson, once a choirboy at St John’s, came to rededicate the church.

Inside The Building

Among those items designed by Sir Ninian Comper:

- Baldachino over the High Altar;

- four stained glass windows in the Lady Chapel which were installed in 1958, the work being carried out by John Bucknall, great-nephew of Sir Ninian Comper. Sir Ninian’s monogram of a strawberry is shown at the bottom of two of the windows;

- canopy above the altar of the Lady Chapel and the bas relief of the Virgin and Child on the wall behind it;

and by Sebastian Comper:

- the main body of the Church where he raised the walls by nine feet and added eight clerestory windows on either side to let in more light;

- six stained glass windows in the Apse. The work was executed by A. L. Wilkinson. The three central ones were in place for the Rededication of the Church in 1951 and the others were installed a year later;

- Stations of the Cross;

- choir gallery erected in 1954.

In addition we have two windows executed by John Bucknall in 1963 in the North Aisle. His monogram of strawberries and a bee can be seen at the bottom of St Ursula’s window. We are also very lucky to have some older stained glass in St John’s. The earliest is hidden by the organ and generally cannot be seen but it is the work of master glass painter A. L. Moore (1849 to 1939). Arthur Louis Moore was one of nine children of a Clerkenwell clockmaker (possibly John Moore mentioned above!). The firm he started in 1871, with a Mr S. Gibbs, produced in its time at least 1,000 windows in the British Isles and 100 overseas. The earliest glass that can be seen are the windows in the South Aisle and are the work of the firm C. E. Kempe & Co which was founded in 1868. The founder, Charles Eamer Kempe, was one of the great stained glass workers of the 19th century and very much influenced by medieval stained glass. John Lisle, who designed St John’s windows, was Kempe’s chief designer during his lifetime and became one of the directors of the firm on Kempe’s death. The Kempe monogram of a wheatsheaf and tower can be seen in the left-hand corner of one of the windows. The Organ came from Camden Church, Peckham where it was often used for recitals. When the bombing began in the Second World War, N. P. Mander Ltd were given the task of rescuing organs from churches that had been destroyed and giving them to churches that needed them. St John’s was the first church ready to receive one.

St John’s Parish Archivist

Leave a Reply